Are nasal steroid sprays safe?

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of our group specialist practice

Nasal steroid sprays are frequently prescribed by general practitioners, pediatricians, and ENT specialists for a condition called allergic rhinitis. Rhinitis refers to inflammation of the nasal lining that causes a runny nose or nasal blockage. Often, there is accompanying sneezing and itching. When there is a demonstrated allergy underlying the rhinitis, it is termed allergic rhinitis. Allergic rhinitis can be seasonal or perennial depending on the allergens responsible. In Singapore, the most common allergen is house dust mites. This is present throughout the year and therefore causes perennial allergic rhinitis.

In the local context, treatment for allergic rhinitis has to be year-long without any “therapeutic holidays”. The question of drug safety is paramount and often a topic of intense discussion with all my patients and their carers.

Nasal steroid sprays

There are several different nasal steroid preparations available. These include:

- Avamys (Fluticasone Furoate)

- Flixonase (Fluticasone Propionate)

- Nasacort (Triamcinolone Acetonide)

- Nasonex (Mometasone Furoate)

- Rhinocort (Budesonide)

Recently, a steroid and antihistamine mixture has gained popularity – this is called Dymista which is a combination of Fluticasone Propionate and Azelastine.

Avamys, Nasacort, and Nasonex are licensed in Singapore for use in children from the age of 2. Flixonase is licensed for children 4 years and older and Rhinocort is for children 6 years and above. Dymista can be prescribed to patients 6 years and older.

What are the side effects of nasal steroids?

The use of nasal steroids is associated with side effects. These include common ones such as:

- Nasal irritation, soreness, burning, and dryness

- Nose bleeds

- Throat irritation (pharyngitis)

- Headache

And rarer ones such as:

- Nasal septal ulcers

- Fungal infections

- Raised intraocular pressure (glaucoma)

- Cataracts

Most of the common side effects are entirely reversible.

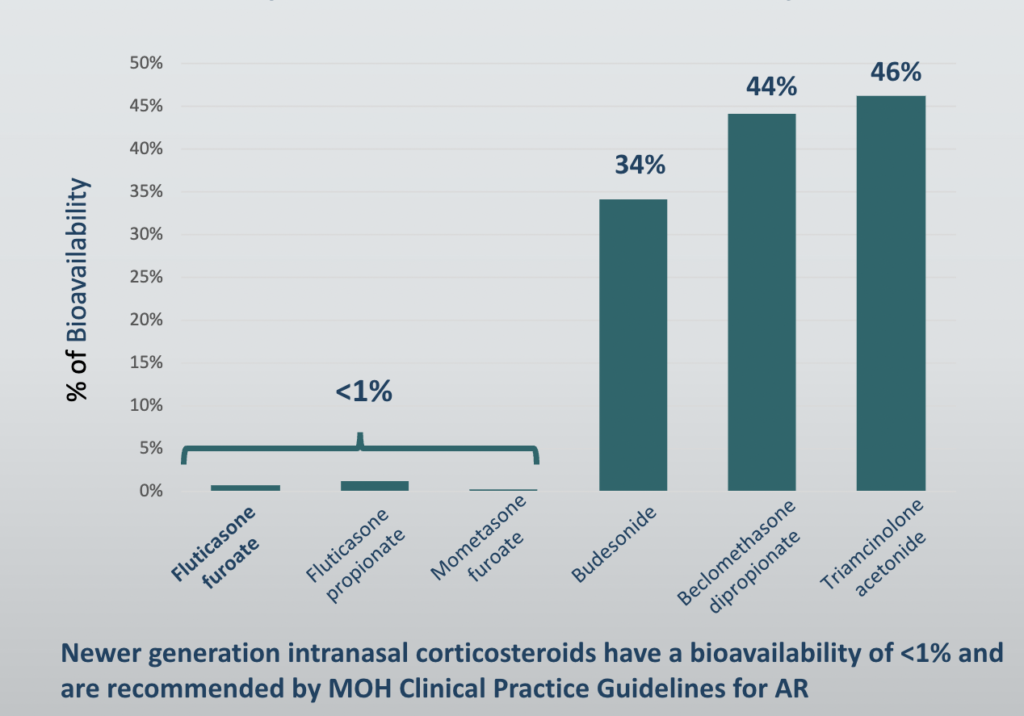

The real concern with nasal steroids is the amount absorbed into the body or what is termed the bio-availability. Some data suggest that twice-daily dosing with intranasal steroids increases the bioavailability more so than once-daily dosing with the same total daily dose. It is the availability of steroids in the body that can cause harm.

The chart above shows that the bioavailability of newer generation nasal steroids i.e. Nasonex (Mometasone Furoate), Avamys (Fluticasone Furoate), and Flixonase (Fluticasone Propionate) is much lower than Rhinocort (Budesonide) and Nasacort (Triamcinolone Acetonide). The newer generation steroids that are absorbed tend to be degraded quickly by the liver when they first pass through this important detoxifying organ.

It is interesting to note that Dymista which is a combination of Fluticasone Propionate with Azelastine actually confers the preparation a 44-61% higher bioavailability than monotherapy with Fluticasone Propionate alone. Also due to its antihistamine content, there is a reported 8% incidence of sleepiness (or hypersomnolence). The prescribing information for Dymista advises that physicians “caution patients against engaging in hazardous occupations requiring complete mental alertness and motor coordination such as driving or operating machinery after use”. This is a little-known fact amongst GPs and specialists.

Do nasal steroids affect growth?

This is a critical question for parents. Many children with allergic rhinitis will need long-term treatment with nasal steroids unless they opt for allergen immunotherapy which offers a ‘ramp out” from this chronic condition.

It has long been known that oral steroids affect growth in children. It was shown that oral steroids affect what is known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis which is the hormonal control of growth. The effects of steroids on the HPA axis (using a test called the short ACTH stimulation test) were used as a surrogate for the deleterious effects of absorbed inhaled or intranasal steroids on growth. However, in the 1990s, evidence mounted that growth could be affected without any detectable change in the HPA axis. So in 1998, the USFDA mandated that all inhaled and intranasal steroids should have information on growth suppression in the adverse reactions and precautions sections of their data sheets.

The data on growth suppression is sparse but two trials have been informative. In 2000, a trial of 98 pre-pubescent children randomised to receive either 100 mcg of Mometasone (1 puff daily in each nostril of Nasonex) or placebo for 1 year showed no evidence of height suppression in the treated group compared to placebo. See Pediatrics (2000) Feb;105(2): E22. In 2014, a clinical trial of 373 pre-pubescent children treated with either 110 mcg of Fluticasone Furoate (2 puffs daily in each nostril of Avamys) or placebo for a year showed that children in the treatment group grew 2.7 mm less. See J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2014) Jul-Aug;2(4):421-7.

There are issues with comparing these trials and their applicability to clinical practice. Most clinicians would titrate the dose of intranasal steroids to the lowest dose to achieve symptom control. With Avamys, this can be 1 puff daily (total dose 55mcg) or even less if every other day dosing is advised. Nasonex too can be reduced to every other day dosing, although it would appear once-daily dosing for a year is safe enough.

Are there conditions in which nasal steroids should be used with caution?

There are a few conditions in which the use of nasal steroids should be used with caution. The conditions are rare amongst younger patients who need nasal steroids for allergic rhinitis.

- Glaucoma. Glaucoma is due to raised pressure within the eyeball, or intraocular pressure (IOP). Nasal steroids – particularly the older generation ones – can raise IOP.

- Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is a rare condition that causes central visual blurring in the affected eye. It is due to the accumulation of fluid in part of the retina called the macula. It is most commonly due to oral steroid use. However, recent reports have shown an association with the use of nasal steroids. I have seen only one patient with CSCR and allergic rhinitis. Needless to say, he did not get any nasal steroids after a very brief discussion!

Can nasal steroids be used safely in Pregnancy?

This is a question that has gone begging for decades. It is largely unethical to perform randomised trials of intranasal steroids on pregnant women so much has to be inferred from data derived from animal studies. Budesonide was the first to gain acceptance amongst clinicians treating pregnant women with intractable allergic rhinitis. The USFDA designated intranasal Budesonide (Rhinocort) a USFDA category B rating based on data from inhaled Budesonide in pregnant women. This was in the face of animal data suggesting birth defects (teratogenicity). It was not until 2016 that a trial was published looking at intranasal Triamcinolone (Rhinocort) in pregnant women. No birth defects were found but there was a small increase in respiratory defects. See J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138:97-104. The findings of this study were confounded by the lack of data on the smoking status and alcohol consumption of the women included.

Since 2015, the USFDA category rating has been discontinued and pharmaceutical companies have to publish their safety data. Thus far, none of the newer generation intranasal steroids have any human data on safety in pregnancy, and it is unlikely this will change anytime soon!

So what does one do in practice?

The principle of titrating the dose of nasal steroids to the minimum necessary dose to effect symptom control is key. Concomitant use of saline irrigation may allow for steroid dose de-escalation. I also discuss “steroid-sparring” and “disease-modifying” strategies such as oral allergen immunotherapy for moderate-severe cases.

Nasal steroid therapy is the main pillar of allergic rhinitis treatment. The benefits of treating allergic rhinitis with nasal steroids need to be weighed against the cost of treatment and the burden of untreated disease. For example, poor quality sleep may hamper growth more than growth suppression from nasal steroid therapy.

The principle of titrating the dose of nasal steroids to the minimum necessary dose to effect symptom control is key. Concomitant use of saline irrigation may allow for steroid dose de-escalation. I also discuss “steroid-sparring” and “disease-modifying” strategies such as oral allergen immunotherapy for moderate-severe cases.

In patients who are on long-term therapy, especially those on concomitant inhaled steroids for asthma, I keep track of growth in collaboration with their paediatricians.

Finally, I do try and avoid inhaled steroids in pregnant women. In severe cases, for those who have not responded to pregnancy-safe anti-histamines, I do suggest nasal irrigation with Budesonide (Pulmicort Respules) for short periods of up to 10 days.

Share this blog via: